Understanding the Banyan Beyond Symbolism

India’s national tree is not defined by height or ornamentation. It is defined by how it behaves over time.

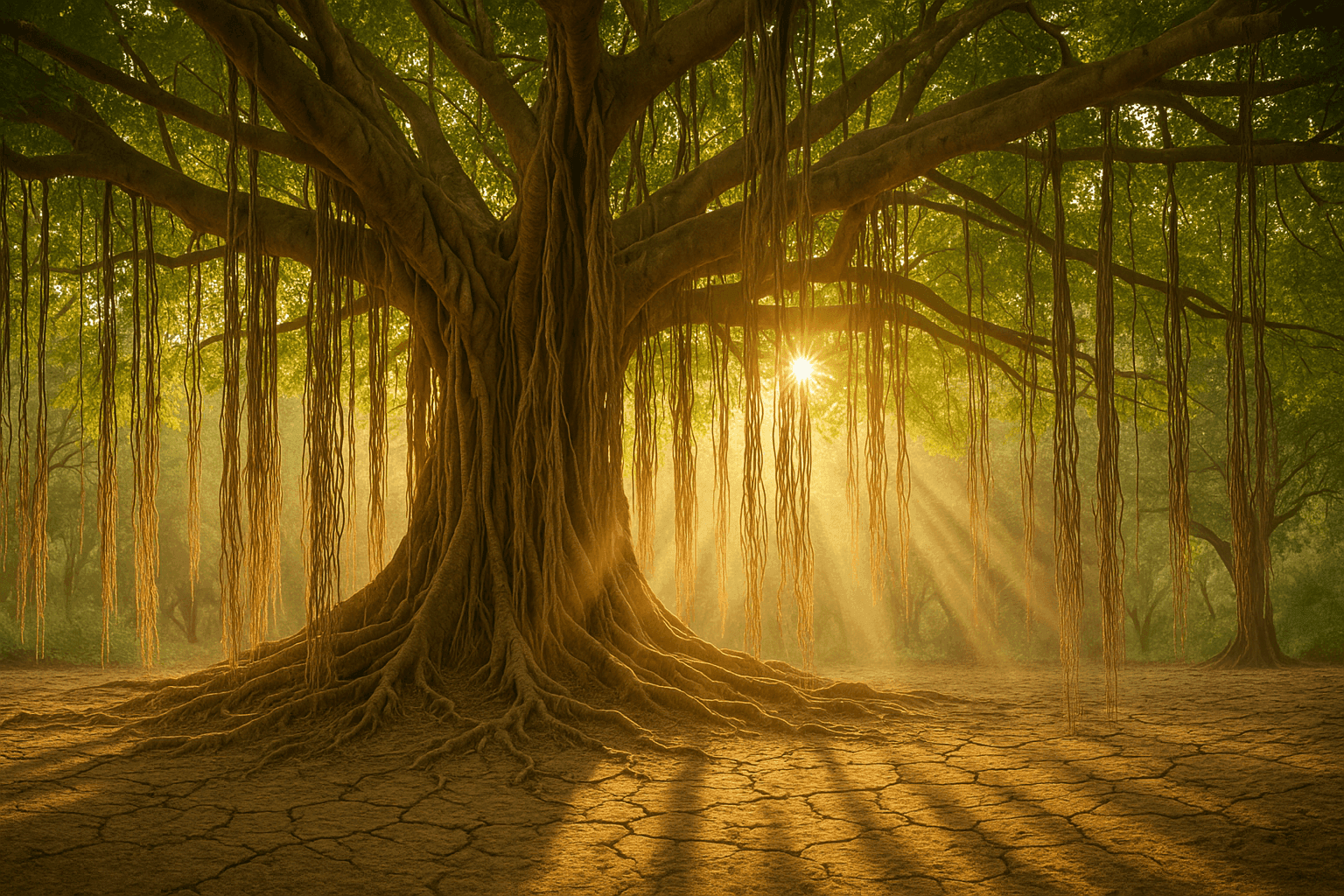

The banyan (Ficus benghalensis) is a tree that grows outward rather than upward, slowly turning open land into shared, shaded space. Its form resists boundaries. Its presence reshapes the ground beneath it. Over decades, sometimes centuries, it becomes less of an object and more of a place.

This quality of persistence is what gives the banyan relevance today, not just as a national emblem, but as a living ecological system.

A tree that grows differently

Most trees compete vertically for light. The banyan takes a different path.

Instead of relying on a single trunk, it produces aerial roots that descend from its branches. When these roots reach the soil, they anchor, thicken, and eventually function as additional trunks. Over time, one tree becomes a network of supports, allowing the canopy to spread horizontally across a wide area.

This unusual growth pattern explains why some banyans are among the widest trees on Earth and why mature individuals often resemble entire groves rather than solitary trees. The species’ structure prioritises stability and longevity rather than speed, a trait that becomes clear when observing how banyans develop over long timeframes.

You don’t stand next to a banyan. You move within it.

Creating its own microclimate

A mature banyan does more than provide shade.

Its layered canopy filters sunlight rather than blocking it completely. Ground temperatures beneath it are noticeably lower. Soil retains moisture longer. Evaporation slows, and temperature swings become less extreme. Together, these effects create a stable microclimate that supports plants, animals, and people.

In hot regions, this difference is not decorative. It determines whether understory vegetation survives, whether animals find refuge during extreme heat, and whether outdoor spaces remain usable at all. The role of large-canopy trees in moderating heat and improving liveability is central to discussions around urban forestry and climate-responsive landscape design.

The banyan’s contribution is quiet, cumulative, and deeply local.

An ecological anchor in the landscape

The banyan’s importance extends well beyond its physical presence.

As a fig species, it produces fruit across much of the year rather than in a short seasonal window. This continuous availability makes it a dependable food source for birds, bats, insects, and small mammals, especially during periods when other trees are not fruiting. Because of this, fig trees often act as ecological anchors, holding food webs together through scarcity.

In fragmented or degraded landscapes, a single mature banyan can become a refuge. It reconnects ecological interactions disrupted by roads, agriculture, or expanding settlements. The broader role of figs as keystone resources is widely recognised in discussions of tropical biodiversity, particularly in regions under ecological pressure.

This is why banyans often appear disproportionately important despite their relatively low numbers.

Carbon, without overclaiming

Banyan trees store carbon in their large biomass, and they do so for long periods of time. Their size and lifespan mean carbon remains locked in living tissue for decades, sometimes centuries.

What they do not do is grow quickly. Banyans are not suited to short-term carbon projects or rapid offset calculations. Their contribution is slow, durable, and tied to landscape stability rather than yield.

This distinction matters. Climate responses increasingly differentiate between fast-growing mitigation tools and long-lived systems that support adaptation, resilience, and risk reduction, a framing that runs through current thinking on climate impacts and adaptation.

The banyan belongs firmly in the latter category. Its value lies in permanence, not speed.

How banyans became social spaces

Across India, banyans appear in village centres, near crossroads, along old travel routes, and at the edges of agricultural land. These locations were not chosen for symbolism.

They were chosen because banyans offered dependable shade, open gathering space, and continuity. Meetings happened beneath them because the space endured. Markets formed there because people could gather without discomfort. Travellers rested there because the tree was visible, familiar, and reliable.

Over time, stories accumulated and rituals followed. But function came first. This long association between banyans and human settlements is evident in historical botanical records and landscape descriptions of the Indian subcontinent, including those maintained by institutions like the Botanical Survey of India.

Meaning grew because the tree remained.

Friction with modern development

In contemporary cities, banyans are often treated as inconvenient.

Their expansive root systems conflict with roads and underground utilities. Their wide branches demand space that dense developments rarely provide. When planted without long-term planning, banyans are frequently subjected to aggressive pruning that weakens their structure and reduces their ecological value.

This tension is not a failure of the tree. It is a mismatch of timescales.

Banyans operate for decades. Urban development often operates for years.

Where banyans still make sense

Despite these challenges, banyans continue to have a place in modern landscapes.

They thrive in large public spaces, institutional campuses, temple grounds, buffer zones, and peri-urban areas where land use is stable and long-term protection is possible. In such contexts, they provide benefits that smaller ornamental trees cannot replace.

Planting a banyan is not a landscaping choice. It is a commitment to continuity.

Why national trees still matter

National trees are often treated as symbolic footnotes. In reality, they reflect what a society chooses to value in its landscapes.

India’s choice of the banyan signals respect for endurance, shared space, and coexistence across generations. These are not abstract ideals. They are ecological traits expressed through a living system that continues to function under pressure.

The banyan does not demand attention. It simply persists.

That persistence is what makes it worthy of representation.

FAQs

1. Why is the banyan the national tree of India?

The banyan was chosen as India’s national tree because of its long lifespan, wide canopy, and ability to support diverse ecosystems. It represents endurance, stability, and coexistence across generations.

2. What is the scientific name of the banyan tree?

The scientific name of the banyan tree is Ficus benghalensis. It belongs to the fig family and is native to the Indian subcontinent.

3. How long does a banyan tree live?

Banyan trees can live for several centuries under favourable conditions. Their long lifespan is one of the reasons they play such an important ecological and cultural role.

4. How does a banyan tree grow so wide?

Banyans grow aerial roots from their branches, which reach the ground and develop into supporting trunks. This allows the tree to spread horizontally over large areas.

5. Do banyan trees support biodiversity?

Yes. Banyan trees provide food, shelter, and nesting space for birds, bats, insects, and small mammals. Their year-round figs make them especially important for wildlife.

6. Are banyan trees good for urban environments?

Banyans can be suitable for cities only where enough space and long-term planning exist. They are better suited to large public spaces, campuses, and peri-urban areas than dense city streets.

7. Do banyan trees help with climate change?

Banyan trees contribute mainly through heat reduction, soil stability, and long-term carbon storage. They support climate adaptation rather than rapid carbon sequestration.

8. Why are banyan trees often found in village centres?

Historically, banyans were preserved in village centres because they provided reliable shade and open gathering space. Social and cultural practices developed around these functional spaces over time.

9. Can banyan trees be planted anywhere?

No. Banyans require significant space to grow safely and should only be planted where land use is stable for decades. Poor placement often leads to excessive pruning and tree stress.