Carbon is inside your body, in the air you breathe, in plants, in the ocean, in soil, and even in rocks. But it never just sits there. It moves. That continuous movement of carbon through the air, water, land, living things, and rocks is called the carbon cycle. Understanding the carbon cycle is essential if you want to really understand climate change, carbon footprint, and net-zero targets.

1. First Things First: What Is Carbon?

-

Living things (plants, animals, you)

-

Fossil fuels (coal, oil, gas)

-

Atmospheric gases (like carbon dioxide, CO₂)

-

Oceans (dissolved carbon)

-

Rocks (limestones, carbonates)

Carbon atoms can join with other elements to form molecules such as:

-

CO₂ (carbon dioxide) – 1 carbon + 2 oxygen

-

CH₄ (methane) – 1 carbon + 4 hydrogen

-

C₆H₁₂O₆ (glucose) – sugar in plants

Because carbon can form so many different molecules, it is sometimes called the “backbone of life.”

2. What Is the Carbon Cycle? (Simple + Scientific Definition)

Simple definition

The carbon cycle is the natural process that moves carbon between the atmosphere, oceans, land, plants and animals, soil, and rocks.

Scientific definition

The carbon cycle is a biogeochemical cycle — “bio” (life), “geo” (earth), and “chemical” — describing how carbon is exchanged among Earth’s major reservoirs (storage pools) through physical, chemical, and biological processes. NASA’s Earth Observatory and NOAA both describe it as a key system that keeps Earth habitable and regulates climate.

So the carbon cycle is not just a diagram in a textbook — it is Earth’s life support system.

3. Carbon Reservoirs: Where Is Carbon Stored?

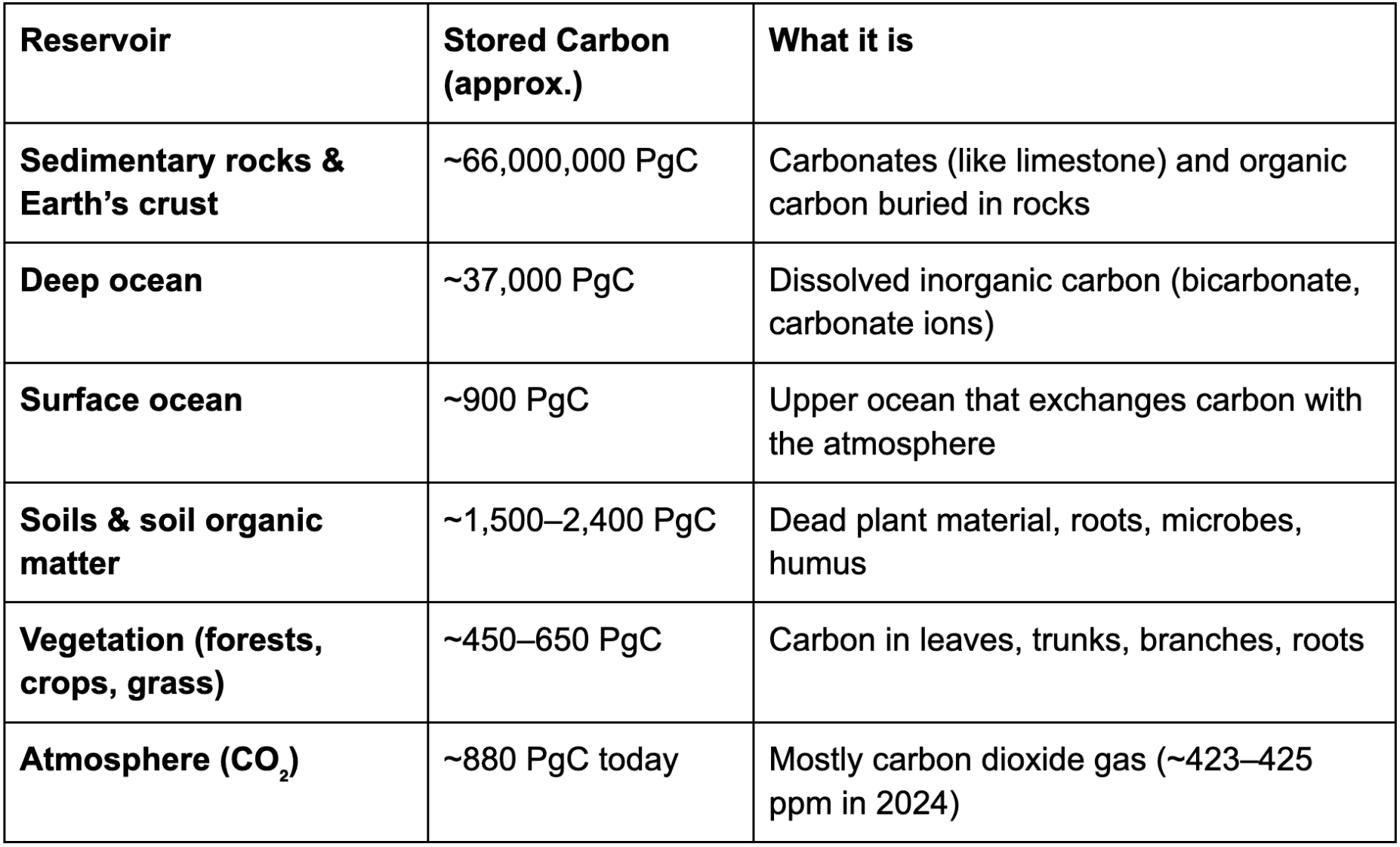

A reservoir is basically a “storage place” for carbon. Different reservoirs hold very different amounts of carbon.

Scientists usually measure carbon in PgC (petagrams of carbon), where 1 PgC = 1 billion tonnes of carbon.

Approximate sizes of major carbon reservoirs:

Sources: NASA, Global Carbon Project, IPCC AR6 Chapter 5, Our World in Data.

Notice something important: The atmosphere stores much less carbon than rocks, oceans, or soils — but small changes in atmospheric carbon can cause large changes in temperature.

4. Carbon Fluxes: How Carbon Moves Between Reservoirs

Examples of fluxes:

-

CO₂ absorbed by plants during photosynthesis

-

CO₂ released during respiration and decay

-

Carbon dissolved into or released from the ocean

-

Carbon stored in or released from soils

-

Carbon locked into rocks through sedimentation

In pre-industrial times (before ~1750), these fluxes were roughly balanced. According to IPCC AR6, global natural fluxes looked roughly like this:

-

Land plants taking in CO₂ (photosynthesis): ~120 PgC/year

-

Respiration + decay returning CO₂: ~120 PgC/year

-

Ocean absorbing CO₂ from air: ~80 PgC/year

-

Ocean releasing CO₂ back: ~80 PgC/year

Result: Atmospheric CO₂ stayed stable at around 280 ppm for thousands of years.

5. The Fast Carbon Cycle (Years to Centuries)

It mainly involves:

-

Atmosphere

-

Land plants & animals

-

Soils

-

Surface ocean

NASA and NOAA describe this as the living, breathing part of the Earth system.

5.1 Photosynthesis – Carbon Goes Into Plants

Plants, algae, and phytoplankton take in CO₂ from the air or water and, using sunlight, make sugars.

Basic equation:

CO₂ + H₂O + sunlight → glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆) + O₂

-

Land plants absorb about 120 PgC/year.

-

Marine phytoplankton also absorb large amounts of CO₂ in the upper ocean.

This is how carbon from the atmosphere becomes food.

5.2 Respiration – Carbon Returns to the Air

Plants, animals, and microbes break down sugars during respiration:

Glucose + O₂ → CO₂ + H₂O + energy

-

This process releases CO₂ back to the atmosphere.

-

The total respiration + decay flux is also about 120 PgC/year, almost balancing photosynthesis in natural conditions.

So plants both take in CO₂ (during the day) and release some back (all the time), but over large areas and seasons, they act as a net sink when growing.

5.3 Decomposition – Nature’s Recycling

When plants and animals die:

-

Bacteria and fungi break down their tissues.

-

This releases CO₂ (and sometimes methane, CH₄, in low-oxygen environments like wetlands).

-

Part of this dead material becomes soil organic carbon, adding to the soil reservoir.

So soils are both sinks (storing carbon) and sources (releasing carbon), depending on climate, land use, and farming methods.

5.4 Ocean–Atmosphere Exchange

The surface ocean constantly exchanges CO₂ with the atmosphere:

-

Cold water dissolves more CO₂.

-

Warm water dissolves less CO₂.

Each year:

-

The ocean absorbs ~80 PgC from the atmosphere.

-

It releases a similar amount back.

This is why polar and sub-polar oceans are strong carbon sinks, while some tropical oceans can be sources.

6. The Slow Carbon Cycle (Thousands to Millions of Years)

The slow carbon cycle is like the planet’s long-term thermostat. It works over thousands to millions of years.

It mainly involves:

-

Rocks

-

Deep ocean

-

Plate tectonics & volcanoes

6.1 Weathering of Rocks

CO₂ + H₂O → H₂CO₃

This slightly acidic water:

-

Reacts with silicate rocks.

-

Breaks them down (chemical weathering).

-

Washes bicarbonate and other ions into rivers.

-

Rivers carry them to the ocean.

This process slowly removes CO₂ from the atmosphere and stores it in dissolved form in the ocean.

6.2 Sedimentation and Rock Formation

-

Marine organisms (like corals and shellfish) use dissolved carbon to make calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) shells.

-

When they die, their shells and skeletons sink to the seafloor.

-

Over millions of years, these become limestone and carbonate rocks.

This locks carbon away for geological timescales (millions of years).

6.3 Subduction and Volcanic Activity

-

Oceanic crust with carbonate rocks can be pushed down (subducted) into the mantle.

-

Under high heat and pressure, some of this carbon is converted back to CO₂.

-

CO₂ is then released back into the atmosphere through volcanic eruptions.

Over very long time periods, this slow cycle keeps Earth’s climate within a range where life is possible. NASA’s carbon cycle feature explains this “thermostat” effect.

7. How Humans Have Changed the Carbon Cycle

For thousands of years, natural sources and sinks were roughly balanced. Then came large-scale fossil fuel burning and deforestation.

7.1 Human Emissions Today

According to the Global Carbon Budget 2024:

Total CO₂ emissions (2024): ≈ 41.6 billion tonnes CO₂/year

-

Fossil fuels & cement: ~37.4 billion tonnes CO₂/year

-

Land-use change (deforestation, etc.): ~4.2 billion tonnes CO₂/year

That’s roughly 11.3 PgC/year added to the cycle by humans.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) reported that this has pushed atmospheric CO₂ to ~424 ppm in 2024, with a record annual increase of about 3.5 ppm, the largest since records began in 1957.

For comparison:

Pre-industrial CO₂ ≈ 280 ppm

2024 CO₂ ≈ 424 ppm

That’s about a 52% increase in atmospheric CO₂.

7.2 Where Do Human Emissions Go?

The Global Carbon Budget shows that, on average over the last decade:

-

About 46–48% of human CO₂ emissions stay in the atmosphere (raising CO₂ concentration).

-

About 23–30% is absorbed by the ocean (ocean carbon sink).

-

About 25–30% is absorbed by land ecosystems (forests, soils).

So roughly half of what we emit is still being “helped” by nature’s sinks. But that help is under stress.

8. Carbon Sinks, Carbon Sources, and Sink Weakening

-

A carbon sink absorbs more CO₂ than it releases (e.g., healthy forest, ocean).

-

A carbon source releases more CO₂ than it absorbs (e.g., burning coal, deforested land).

Right now:

-

The ocean and land together absorb about half of our CO₂ emissions each year.

-

But research shows climate change is starting to weaken these sinks, especially on land.

A 2025 study in Nature found:

-

Climate change has reduced sink efficiency, adding about 8.3 ± 1.4 ppm extra CO₂ to the atmosphere since 1960 compared to a stable-sink world.

-

Large parts of Southeast Asian and South American tropical forests are already switching from sinks to sources due to heat, drought, and deforestation.

This is extremely important:

If sinks get weaker, more of each year’s emissions stay in the atmosphere → faster warming, even if our emissions stay the same.

9. Ocean Carbon and Ocean Acidification

But when CO₂ dissolves in seawater, it forms carbonic acid:

CO₂ + H₂O → H₂CO₃

This lowers the pH of the ocean — a process called ocean acidification.

Consequences (from NOAA):

-

Fewer carbonate ions available for corals, shellfish, and some plankton to build shells.

-

Weaker coral reefs → less coastal protection and biodiversity.

-

Changes in marine food webs, which also impact the biological carbon pump (the way plankton move carbon into the deep ocean).

So the ocean is doing us a favour by absorbing CO₂, but it is paying a heavy price.

10. Carbon Cycle–Climate Feedbacks

The carbon cycle doesn’t just respond to climate — it also drives climate. This two-way interaction is called a feedback.

The IPCC AR6 Chapter 5 lists several important carbon–climate feedbacks:

10.1 Positive (Amplifying) Feedbacks

-

Permafrost thaw Frozen soils in the Arctic contain huge amounts of old carbon. As they thaw, microbes decompose this carbon and release CO₂ and CH₄.

-

Soil respiration Higher temperatures make microbes more active, so they break down soil organic matter faster, releasing more CO₂.

-

Forest dieback and fires Heatwaves and drought can kill trees or increase wildfires, turning forests from sinks into sources.

-

Warm oceans Warm water holds less dissolved CO₂, so the ocean’s ability to take up CO₂ decreases.

All these feedbacks increase atmospheric CO₂ for a given human emission level.

10.2 Negative (Dampening) Feedbacks

- CO₂ fertilization Higher CO₂ can stimulate plant growth, especially in some regions, causing extra carbon uptake. But this effect is limited by nutrients, water, and heat stress, and may weaken over time.

Overall, Earth system models show that positive feedbacks dominate, meaning they amplify warming rather than reduce it.

11. Carbon Cycle and the Idea of a “Carbon Budget”

Because CO₂ stays in the atmosphere for a very long time and the carbon cycle controls how fast it is removed, climate scientists use the concept of a carbon budget:

The carbon budget is the total amount of CO₂ humans can emit while keeping global warming below a certain temperature limit (like 1.5°C or 2°C).

IPCC AR6 shows that there is a near-linear relationship between cumulative CO₂ emissions and global warming.

This is why:

-

To stop warming from increasing further, global net CO₂ emissions must go to zero.

-

If we keep emitting, even at lower levels, temperature will keep rising.

So the carbon cycle sets the rules of the game for climate policy.

12. Why Should a 10th Grader Care About the Carbon Cycle?

Because it connects everything:

-

Your food (photosynthesis, soil carbon)

-

The air you breathe (CO₂ levels)

-

The weather and climate (greenhouse effect)

-

The health of forests and oceans

-

Your future — jobs, water, food security, disasters

When people talk about:

-

Carbon footprint

-

Net-zero

-

Carbon credits

-

Reforestation

-

Decarbonisation

…they are all talking, in some way, about how we interact with the carbon cycle. If we understand how the cycle works, we can:

-

Reduce emissions intelligently

-

Protect and restore carbon sinks (forests, soils, oceans)

-

Design better policies, technologies, and lifestyles

You can’t solve climate change without understanding the carbon cycle.

Quick FAQs

1. What are the two main types of carbon cycle?

-

Fast carbon cycle – between atmosphere, plants, animals, soil, and surface ocean; operates over years to centuries.

-

Slow carbon cycle – between rocks, deep ocean, and atmosphere; operates over thousands to millions of years.

2. Why is the slow carbon cycle called Earth’s thermostat?

Because processes like rock weathering and carbonate formation slowly remove CO₂ from the atmosphere and store it in rocks, helping regulate temperature over millions of years.

3. How have humans disturbed the carbon cycle?

By adding ~41–42 billion tonnes of CO₂ per year from burning fossil fuels and changing land use, much faster than natural processes can handle.

4. What is a carbon sink?

A reservoir that absorbs more carbon than it releases, like healthy forests, oceans, and peatlands.

5. What is ocean acidification?

When the ocean absorbs CO₂, it forms carbonic acid, lowering the pH and making it harder for corals and shell-forming animals to survive.

6. How does this connect to “net-zero”?

Net-zero means we stop adding more CO₂ to the atmosphere than Earth’s sinks can safely absorb. That requires cutting emissions and protecting/boosting natural sinks.